Picture that vast, sprawling family tree of Christianity we explored in my article defining Protestantism, which if you haven't read, It is definantlty worth the read. That said, now, a new term branches from this tree: Evangelicalism. But what does it mean? Is it a movement, a theology, or a cultural label? Its fluidity makes it elusive and confusing, often used to describe everything from conservative Bible-thumpers to progressive social reformers. In this article, I'll clash the competing definitions of Evangelicalism, trace its historical and theological threads, and propose a definition that captures its essence and help with its clarity.

The Elusive Nature of Evangelicalism

Unlike Protestantism, which we rooted in a specific historical event, Evangelicalism feels like any ivy stretching across denominations, eras, and even continents. It’s heard in the fervent sermons of a Southern Baptist preacher, the worship songs of Hillsong, or the Bible studies of charismatic Catholics in Latin America. Its versatility is a strength, but also a challenge. To define it, we must understand its many uses, from it's historical roots to how it is expressed and understood today, and then come to a definition.

Let’s begin by examining the four primary ways “Evangelical” is used today, each offering a piece of the puzzle. We’ll test their strengths, probe their weaknesses, and weave them together to find a definition that holds.

1. Non-Institutional Christianity

One common understanding casts Evangelicalism as a form of non-institutional Christianity. To clarify this means a faith, church, or denomination not bound by the hierarchies of Catholicism or Protestantism. Picture a church meeting in a repurposed warehouse, with a worship band leading songs projected on a screen, or a house church where believers share testimonies over coffee. These are often non-denominational congregations or networks like Vineyard, Calvary Chapel, or Hillsong, which emphasize a personal faith, contemporary worship, and a direct connection to Jesus. Here, “Evangelical” can implie freedom from tradition, a focus on individual salvation, and a passion for spreading The Gospel.

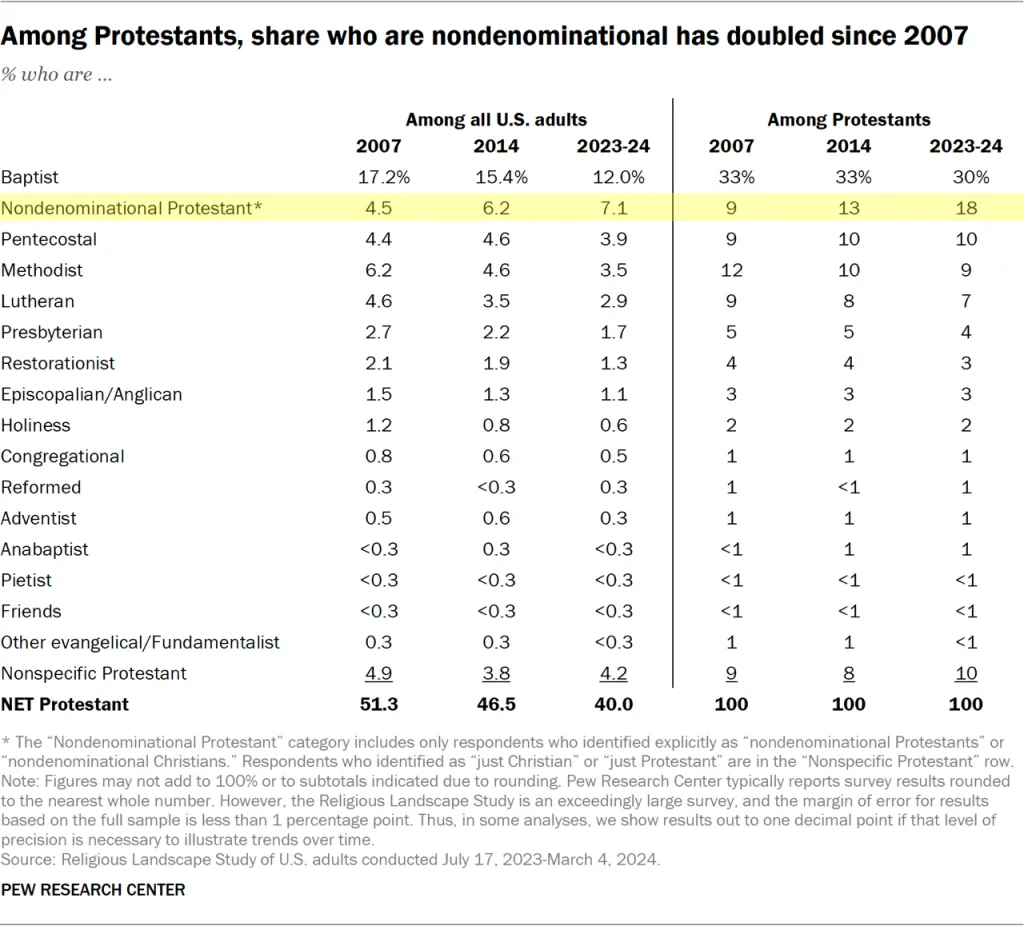

This definition resonates with the individualistic nature of Americans. Non-denominational churches, which now account for a significant portion of American Christianity (18% of U.S. Christians attend non-denominational churches, according to Pew Research), often embody this ethos. They prioritize accessibility, cultural relevance, and evangelism, attracting younger generations with dynamic preaching and music. Movements like the Jesus People in the 1960s, which birthed groups like Calvary Chapel, exemplify this.

But this view fails under scrutiny. Non-institutional Christianity is an overly broad category, encompassing groups with wildly different theologies. Some megachurches lean into the prosperity gospel, emphasizing wealth and health, which most Evangelicals would reject as unorthodox. Others, like certain charismatic groups, prioritize spiritual experiences over doctrine, creating tension with more traditional Evangelical commitments. Further more defining Evangelicalism as “non-institutional” can even risk lumping in movements heretical groups, like Unitarian Universalists or New Age-inspired groups that borrow Christian language.

2. Historically Synonymous with Protestantism

Another perspective anchors Evangelicalism in the 16th-century Protestant Reformation, where the term “evangelical” first gained prominence. Rooted in the Greek euangelion (“good news” or “gospel”), it was adopted by reformers like Martin Luther to describe their movement’s focus on the gospel and salvation by grace through faith. Lutherans, in particular, often called themselves “Evangelical Catholics,” seeking to reform the universal church while preserving its apostolic heritage. In his 1517 95 Theses, Luther challenged the sale of indulgences, arguing that salvation rested solely on God’s grace, as he later elaborated in his work On the Babylonian Captivity of the Church:

“For where there is the word of God Who makes the promise, there must be the faith of man who takes it. It is plain, therefore, that the first step in our salvation is faith, which clings to the word of the promise made by God, Who without any effort on our part, in free and unmerited mercy makes a beginning and offers us the word of His promise.”

This emphasis on Scripture’s authority and the gospel’s centrality as the word of God defined the early Protestant movement, particularly in Lutheran and Reformed circles, making “evangelical” a near synonym for “Protestant.”

This view is bolstered by its historical precision. It explains the naming of denominations like the Evangelical Lutheran Church in Germany or the Evangelical Synod of North America, which merged into modern mainline churches. The term captured the reformers’ desire to return to biblical foundations. Figures like Ulrich Zwingli and John Calvin echoed Luther’s gospel focus, with Calvin writing in his Antidote to the Council of Trent, “It is therefore faith alone which justifies, and yet the faith which justifies is not alone” This theology united early Protestant churches, under an evangelical banner.

However, this definition struggles to bridge the gap to modern usage. While it accurately describes the Reformation’s theological core, it excludes many groups now called Evangelical, such as Pentecostals or non-denominational's, which emerged centuries later. Conversely, many modern Protestants, like those in liberal mainline denominations (e.g., the Episcopal Church or United Church of Christ), often reject the “Evangelical” label. The term’s adoption by non-Protestant groups, like charismatic Catholics in the Global South or Messianic Jews, further complicates its Reformation-era roots. While foundational, this perspective is too confined to encompass Evangelicalism’s current scope, resembling a historical artifact more than a living definition.

3. The Great Evangelical Awakenings

A third perspective often ties Evangelicalism to the 18th- and 19th-century revival movements known as the Great Awakenings, which swept through Britain and North America. The First Great Awakening (1730s–1740s), led by figures like Jonathan Edwards and George Whitefield, (Articles coming soon...) emphasized personal conversion and emotional faith. Edwards, in his sermon Sinners in the Hands of an Angry God (an extremely famous sermon), called for a heartfelt response to God’s grace, sparking revivals across the American colonies. The Second Great Awakening (1790s–1840s), with preachers like Charles Finney, doubled down on individual salvation and social reform, fueling movements like abolitionism and temperance. These awakenings birthed new denominations, like Methodism, and revitalized others, like the Baptists, while inspiring global missionary efforts.

This definition captures Evangelicalism’s more dynamic energy. The Awakenings emphasized “born-again” faith, a personal encounter with Christ that became a slogan of Evangelicalism. They also fostered a culture of evangelism, missions, and social change. For example, William Wilberforce, an Evangelical Anglican, led the fight against the slave trade in Britain, driven by his faith. The Awakening had an extreme impact on denominations like the Southern Baptist Convention, which traces its revivalist roots to this era, and in global missionary societies that spread Christianity to Africa and Asia.

However, this view is limited by its historical specificity. Not all modern Evangelicals trace their lineage to the Awakenings. Conservative Lutherans or Anglicans, for instance, may identify as Evangelical. Additionally, the Awakenings’ focus on emotional experience doesn’t fully account for other groups that emphasize doctrinal precision or sacramental worship. This definition is a important, that said it's not the whole story.

4. The Billy Graham Era or Post-Fundamentalist Evangelicalism

The most dominant modern definition links Evangelicalism to a 20th-century movement, shaped by figures like Billy Graham. You see, in the early 20th century, Fundamentalism emerged as a response in order to liberal theology and cultural shifts, like Darwinism and biblical criticism. Fundamentalists, named for The Fundamentals (a twelve volume set of essays outlining orthodox Christian doctrine published 1910–1915), defended biblical inerrancy and traditional doctrine but often became reconized as narrow-minded, rejecting broader cultural engagement. By the 1940s, leaders like Graham sought a different path. They shared Fundamentalism’s conservative theology but embraced a more open, evangelistic approach. Graham’s crusades, starting in 1947, drew millions with a simple gospel message: personal salvation through faith in Christ.

This “neo-Evangelical” movement, as it was sometimes called, emphasized four priorities: biblical authority, personal conversion, evangelism, and cultural engagement. Organizations like the National Association of Evangelicals (1942), Fuller Theological Seminary (1947), and yes even Christianity Today (1956) gave it structure. Graham’s cooperative approach set it apart from the Fundamentalism’s separatism. For example, his 1957 New York City crusade included mainline Protestants and Catholics, a move that shocked Fundamentalists.

This definition is dominate today because it aligns with modern Evangelicalism’s key characteristics: “born-again” faith, a high view of Scripture, and a desire for evangelism. It’s why groups as diverse as Southern Baptists, Assemblies of God (Pentecostal), and some Anglicans identify as Evangelical. In the U.S., about 12% of adults identify as Evangelical, according to Gallup polls, spanning megachurches, small congregations, and even some mainline churches.

Yet, this definition has challenges. Its inter/transdenominational nature makes it feel like a theological stance rather than a unified movement. Additionally, its broad description risks vagueness, as it includes groups with conflicting practices, from liturgical Anglicans to charismatic Pentecostals.

The Transdenominational Challenge

Evangelicalism’s defining feature, and its biggest puzzle, is its transdenominational nature. Unlike Protestantism, which can be clearly defined as the Churches that came from the Protestant Reformation, Evangelicalism isn’t confined to a single historical moment or institutional structure. It spans mainline denominations (e.g., Evangelical Presbyterians), non-denominational megachurches, and even charismatic Catholics or Messianic Jews. It’s less a distinct branch on the Christian tree and more a theological ivy that spans across branches.

This fluidity makes Evangelicalism feel like a descriptor, akin to “orthodox” or “progressive.” A Southern Baptist and an Evangelical Lutheran might both claim the label, despite different worship styles. But this flexibility raises questions. If Evangelicalism includes such diverse groups, does it have a core? And how do we handle its use by groups outside Protestantism, which blends mainline and Evangelical identities, or Messianic Jews, who integrate Jewish practices with Christian faith? The term’s fluidity risks stretching it to the point of meaninglessness, like a theological catch-all.

Toward a Robust Definition

Let’s evaluate the four definitions again. The non-institutional view captures a modern dynamism but lacks theological or historical precision, risking inclusion of unorthodox groups. The Reformation-era view is accurate for its time but too narrow for today’s usage. The Great Awakenings highlight a pivotal moment but miss later developments. The Billy Graham-era definition, while dominant, struggles with its broad scope and cultural baggage.

A widely respected framework comes from historian David Bebbington’s “quadrilateral,” which identifies four core characteristics of Evangelicalism:

- Biblicism: A commitment to the Bible as the ultimate authority, often emphasizing its inspiration or inerrancy. For example, Evangelicals like those in the Southern Baptist Convention affirm the Bible as “truth without any mixture of error.”

- Substitutionary atonement: A focus on Christ’s atoning death on the cross as the heart of salvation. This echoes Reformation theology but is vividly expressed in hymns like “In Christ Alone,” popular across Evangelical churches.

- Conversionism: An emphasis on personal conversion, often described as being “born again.” This is central to Billy Graham’s preaching, where he urged listeners to “make a decision for Christ.”

- Activism: A dedication to evangelism and social engagement, from missionary work to addressing issues like poverty or injustice. This is seen in organizations like World Vision, founded by Evangelicals.

This set of four descriptors offers a theological core that unites this groups. It explains why Baptists, Pentecostals, and many others identify as Evangelical, while allowing for liturgical or charismatic expressions. To avoid vagueness, we must anchor this theologically in history. Evangelicalism’s modern form emerges from the 18th-century Awakenings, which built on Reformation principles, and matures in the 20th-century post-Fundamentalist movement, which added cultural engagement. Unlike Protestantism, a family of churches, Evangelicalism is a movement within and beyond those churches, defined by shared convictions rather than institutional ties. It’s not a denomination but a theological and missional impulse, flowing through Protestant, Catholic, and independent contexts.

Clarifying Misconceptions

This definition helps distinguish Evangelicalism from related movements. Fundamentalists share biblicism but often lack activism, retreating from culture. Liberal mainline churches may embrace social action but downplay conversionism or biblicism, distancing themselves from Evangelicalism. Non-Christian groups like Mormons or Jehovah’s Witnesses, despite occasional Evangelical-like language, diverge theologically, falling outside historic Christianity.

What about groups like Pentecostals, Messianic Jews, or non-denominational churches? Pentecostals, rooted in the 1906 Azusa Street Revival, align with the quadrilateral, especially conversionism and activism. The Assemblies of God, for instance, is a member of the National Association of Evangelicals. Messianic Jews often share biblicism and conversionism but maintain distinct Jewish practices, making them a parallel movement. Non-denominational churches, while often Evangelical in theology, resist labels, complicating their classification.

The Radical Reformation groups, like Anabaptists, also warrant mention. While they share some Evangelical traits (e.g., emphasis on personal faith), their 16th-century rejection of institutional churches sets them apart from Protestantism and, by extension, modern Evangelicalism, which often works within denominational structures.

Why the Definition Matters

Defining Evangelicalism as a transdenominational movement rooted in the Bebbington quadrilateral, with historical ties to the Awakenings and post-Fundamentalist era, preserves its distinctiveness. It avoids conflating it with Protestantism (a specific family of churches), Fundamentalism (a narrower, separatist movement), or liberal Christianity (which prioritizes inclusivity over doctrine). This clarity respects the unique histories of Baptists, Pentecostals, and others, while highlighting their shared theological commitments. It also acknowledges Evangelicalism’s global reach, from African revivals to European confessions, without reducing it to a Western phenomenon.

A Clear Definition of Evangelicalism

Evangelicalism is a transdenominational Christian movement characterized by a commitment to the authority of Scripture, the centrality of Christ’s atoning work, the necessity of personal conversion, and active engagement in evangelism and social reform. Emerging from the 18th-century Great Awakenings and solidified in the 20th-century post-Fundamentalist movement, it builds on the Reformation’s gospel-centered legacy but extends across Protestant and non-Protestant traditions. Unlike Protestantism, defined by the Lutheran, Anglican, and Reformed churches of the 16th-century Reformation, Evangelicalism is a theological and missional movement, uniting diverse believers under shared convictions expressed through the Bebbington quadrilateral: biblicism, crucicentrism, conversionism, and activism.